On the day that the Ashes starts I thought it was about time to do a post on Cricket. I will be writing my weekly round up of the week's sports tomorrow and will be including some thoughts more directly related to the Ashes there.

|

| Billy Beane. Doesn't look like Brad Pitt. |

For many

years Cricket had been dominated by the most simplistic statistical thinking; Averages

and strike rate (and additionally for bowlers – economy rate) were the only

statistics taken into any sort of consideration. The problem with these statistics

is that they take no account of game situation, pitch conditions, overhead

conditions, quality of opposition and type of opposition (i.e., left arm spin,

right arm seam etc). For example, whilst Kevin Pietersen averages a quality 49

in test cricket, his average against left arm spin is a modest 38. Stuart Broad

has an overall bowling average of 31.93, which improves to 27.51 in England but

balloons to 43 in Asia (including two tests against enthusiastic minnows

Bangladesh). Would it not be sensible to consider picking other another batsman

who doesn’t exhibit this weakness when facing quality left arm spin bowling.[3]

Broad’s has struggled in the sub continent for a while now and a large enough

sample size in evidence to suggest that an alternative should be found by

England. Even these simple manipulations of the statistics seem to be beyond

England’s selectors who seem to prefer a rigid team selection to a more

squad-based system where players are picked according to their various

strengths.

|

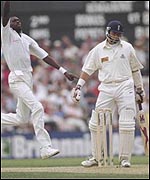

| Alan Wells is dismissed by Curtley Ambrose. Is it better to be picked once and dropped than never to be picked at all? |

Only the

arrival of Nasser Hussain, Duncan Fletcher and the new standard of

professionalism that they brought with them saved English cricket from the

inconsistent selection that had plagued it for so long. Alongside the

consistency required to build a strong team, Fletcher, Hussain and, later,

Vaughan used technology to help England improve and analyze their game. The

rise in professionalism and analysis has coincided with a rise in the England

team’s fortunes. England has sports analysts, Nathan Leamon for tests and Gemma

Broad for ODIs, whose sole role is analyze data and come up with plans to

combat opposition players.

Jimmy

Anderson and Steve Harmison recently spoke on the Tuffers and Vaughan radio

show and highlighted the advanced use of specific plans to individual batsmen

that they faced. When specifically questioned by Mark Chapman as to how he

would get out Ramnaresh Sarwan, for example, Anderson responded that Sarwan is

LBW candidate early on and that he would try to “run on back into him.” To AB

De Villiers the plan would be to “make him play with a straight bat” as he

scores heavily with cross bat shots.

His

answers show that plans to get out different batsmen are created in two ways,

firstly through analyzing any technical deficiency, (in Sarwan’s case above

that he gets his front foot too far across early on and ends up playing round

his pad) and secondly through Hawkeye pitch data and a batsman’s average when

facing balls pitched in certain areas. De Villiers scores heavily when facing

anything short pitched and so the plan is always to keep it up to the bat to

force him to play straight. It must be noted that De Villiers is such a quality

batsman that Anderson’s method of bowling to him is more of a way of

restricting his scoring rather than targeting a weakness.

The use

of Hawkeye and similar ball tracking technologies is at the heart of the new

advance in analytics in cricket. By being able to track the flight and pitch of

every ball bowled in world cricket, statisticians are able to record the strike

rate and average of each batsman in different pitching areas and finishing

points.[6]

For example analysis of the finishing points of a certain bowler could help Eoin

Morgan’s shot selection outside off stump, the pitch map could allow Mitchell

Johnson to locate the pitch (just a tad) more regularly and Jimmy Anderson can

even end up seeing where his deliveries pitch.

Analysis

and research into the game is continuing apace and its only going to accelerate

in the future, so where is it headed? I feel that a squad system is more likely

to become commonplace. Players will be used in a rotation policy slightly

reminiscent of football. This will allow for squad depth in bowling and batting

departments to cover for injuries and allow management to pick teams in a

slightly more horses-for-courses way. These ideas are commonly used in county

cricket with young players picked in short formats of the game to gain

experience and experienced players picked in the more important county

championship matches.[7] Bowlers will

be on limited over counts similar to pitch counts in baseball in order to

manage workloads. Other statistical elements will slowly work themselves into

the game as captains and coach’s search for even more sophisticated ways of

gaining an advantage.

Traditionalists

fearful of the total dominance of cricket by analytics should not worry too

much though. Cricket is a far more cerebral game than baseball and often a

captain’s feel for the game will capture a wicket far more quickly than

stubbornly sticking to a statistical plan that may not be working. Making use

of the statistics in sensible ways is far harder than their creation, so whilst

cricket may be appropriating statistical ideas from baseball the complexity of

cricket will make it harder to totally analyze the value of each decision made.

Cricket is so complex that it will

never be as comprehensively analyzed as baseball but their is definitely some

work that can be done. Digital decision-making may be useful but sometimes a

little analogue thinking can get you a wicket much more cheaply. Or, if you are

an Australian, you can just punch someone in a bar and hope that will put him

off his game.

[1] OPS –on-base plus slugging - is an example of using two old

statistics combined together to form a newer, more accurate measure of a

batters value to the team.

[2] For example in 2006, the Athletics finished with the 5th

best record in Major League Baseball despite having the 24th lowest

payroll of the 30 teams.

[3] For the record, in this case, I think they should consider it, then

forget about it. KP is too good to get dropped. But they should definitely be considering things.

[4] Two famous examples where this strategy paid dividends were Marcus

Trescothick and Michael Vaughan. Trescothick was famously picked for England

after scoring 167 in a low-scoring match at Taunton in front of Duncan Fletcher,

soon to be England coach, despite averaging in the low 30s in his career until

this point. Trescothick went on to average 43.79 in tests and 37.37 in ODIs as

a destructive opening batsman for England. Similarly Michael Vaughan also

performed much better for England than Yorkshire with his test average standing

at nearly 5 runs better than his first class average (41.44 – 36.95).

[5] Unbelievably JJ Ferris took 13/91 in the match and never played again!

[6] Only 3 of the international teams have statisticians at the moment

– India, England and Australia.

[7] England are also following this route with their own T20 side. The

large majority of the side is very young with only KP a regular in the test

side.

No comments:

Post a Comment